Workers in front of the ceramic kiln at A. Apostolides pottery workshop located at the Prison Hill in Corfu. Aristeidis Apostolides Private Collection.

Refugees faced a variety of difficulties when they settled in their new homeland, the main one being their accommodation and the provision of a decent living for their families. Despite the national homogeneity sought by the 1923 Exchange of Populations, the refugees were not instantly assimilated into their host countries.

Their Greek culture was overshadowed by their specific cultural features that differentiated them from the native populations. Mentality, customs, and language contributed to the marginalisation of the refugees, whereas religion and family values initially served as a bridge of communication.

A distinctive feature of loyalty, solidarity and the high national discretion is the denial of food, which offered the Italian administration after the issue Tellini and the Bombing of Corfu, where 35 people injured and 15 people died, on August in 1923.

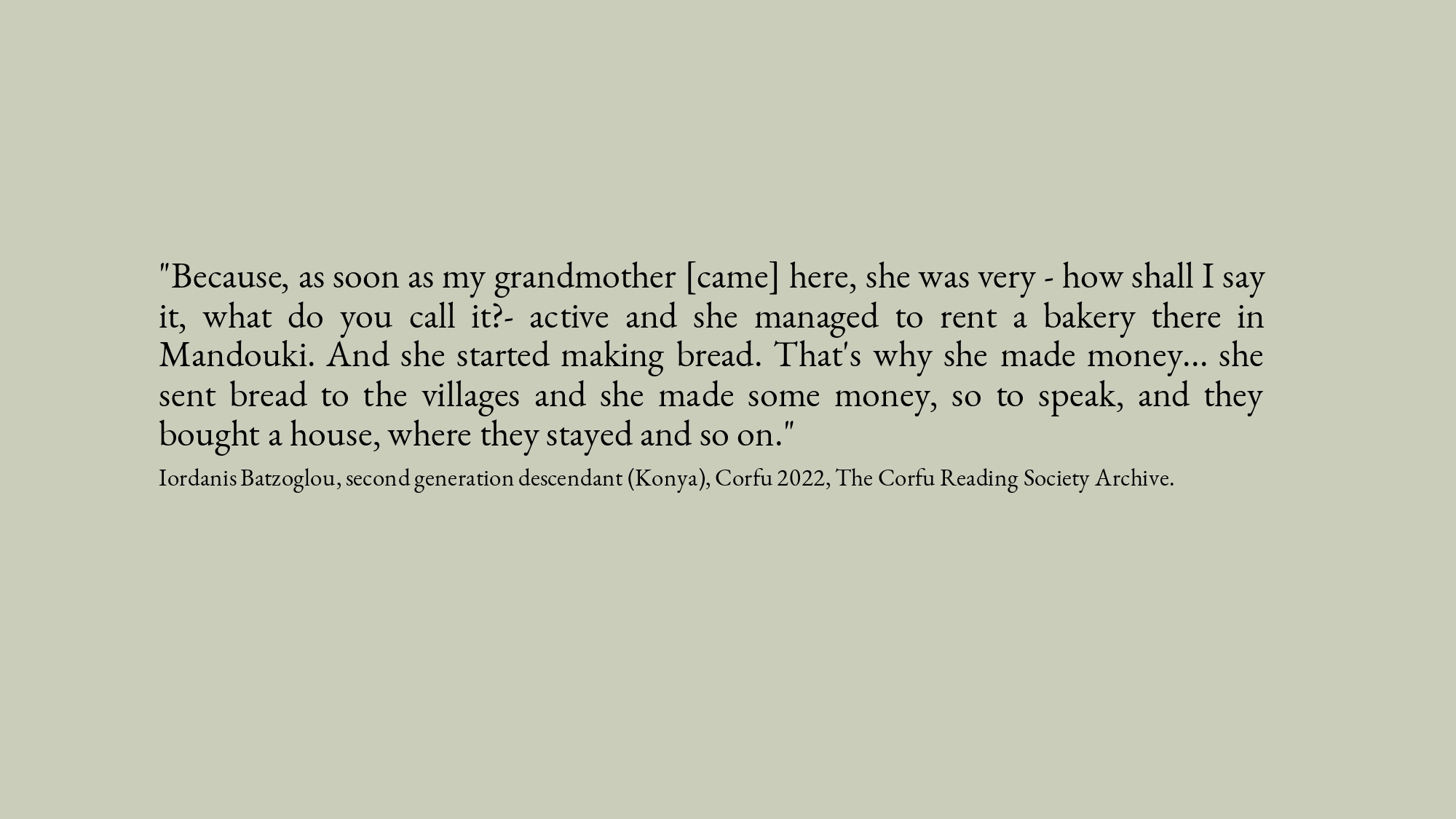

The effective assimilation of the refugees in Greece would be achieved after their permanent settlement and their vocational rehabilitation. Exercising an occupation they were familiar with was a prerequisite for the permanent settlement of refugees in a place. This resulted in many moving to other Greek cities, in order to provide for their families.

According to the data communicated in December 1925 by the Ministry of Hygiene, Welfare and Perception to the Refugee Settlement Commission, there were 1,416,708 refugees in Greece. 832,745 of them were urban refugees (212,778 families) and 583,963 (148,868 families) were rural refugees. It is estimated that 2,240 (720 families) lived in Corfu at the time, 1,493 (481 families) of which were urban refugees and 747 (239 families) were farmers.

Working in the agricultural sector was an unsuccessful solution for the refugees in Corfu. The island did not have sufficient cultivation land and the opportunities for agricultural and livestock farming were scarce. Despite the objective difficulties, it was attempted in the early years to install part of the refugee population in the Corfiot countryside. However, soon the impossibility to exercise farming activity forced them to choose between settling in Corfu town or relocating to another part of the country.

The lack of suitable settlement space and available employment, led in 1924 the Prefecture of Corfu to the conclusion that only 700 people (140 families) could settle on the island. The statements of the Police department of Corfu and of the Chamber of Commerce, which largely reflect public opinion, are typical of this; they considered that there is oversupply of labour force compared to the demand in the sectors of commerce and local industry. The first decades of the 20th century are considered extremely profitable for the sectors of transit trade (import-export) and industrial development.

In Corfu, there are several industrial units and small factories among which flour milling industry, pulp and paper industry, leather industry, oil mill industry, soap industry, a string, rope, and sacs producing factory, and the well-known Aspioti-Elka Graphic Arts S.A., which specialised in chromolithography and etching. During their temporary stay in Corfu, some refugees were temporarily employed in various works on the initiative of the local government. The contribution of the 27 refugees and 13 native people in 1923 to the reconstruction of the orphanage in Spilia was of great importance. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by a fire.

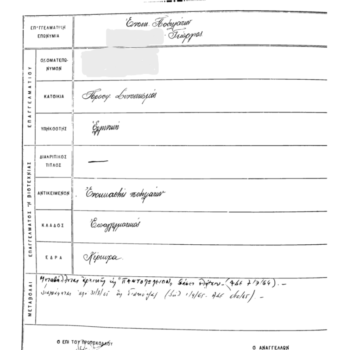

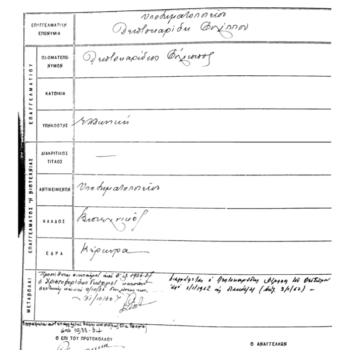

Theodoros Megalomatides (03/01/1935). Eleonora Gavriilidou Private Collection.

The 1928 census records 2,149 refugees in Corfu, 189 of whom arrived on the island before 1922, while 1,960 fled there after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1022. The settlement of the remaining refugees in Corfu was urban, as it only provided permanent accommodation without ensuring some form of occupation. Conflicts between native population and refugees were common, despite the fact that a small number of refugees settled in Corfu, out of a total of 30,000 that arrived on the island. Some Corfiots were very hospitable and supported, cooperated with, and assisted the uprooted Greeks.

Σπυρίδων Μουρατίδης, Κέρκυρα 22/07/2022, Αρχείο Αναγνωστικής Εταιρίας Κερκύρας.

Ministry of National Economy - General Statistics of Greece, Statistical results of the population census of Greece on 15-16 May 1928, Athens, 1935.

Very few refugees managed to retain the occupation they had in their places of origin. A League of Nations report in 1926 states that some refugees were compelled to change their occupation up to six times within the same year.

Employment Male Refugees 1922-1932, The most prevalent occupations of refugees (in descending order) according to the General State Archives, Corfu Registry Archives, Death certificates 1922-1932 (total 181)-Birth certificates 1922-1932 (total 439)-Marriage Registers 1922-1932 (total 234).

It is observed that the occupations of the urban men refugees comprise both unskilled workers that worked in manual labour to earn a living, and craftsmen, merchants, freelancers in general, and others who served in law enforcement. Less often, purely urban occupations are found, such as doctor, dentist, lawyer, pharmacist, veterinary, insurance broker, jeweller, and captain. Similarly, a small number is observed in occupations such as fishmonger, butcher, saddler, flour miller, sailor, lithographer, greengrocer, blacksmith, which, however, seem to have been exercised by a greater number of men refugees than those declared.

Σπυρίδων Μουρατίδης, Κέρκυρα 22/07/2022, Αρχείο Αναγνωστικής Εταιρίας Κερκύρας.

Even the very few refugees that decided to make a living in the countryside of Corfu, engaged mainly in ‘urban occupations’. Of course, some sought to earn their daily bread by cultivating the land and livestock farming, but very few were successful because they lacked know-how and economic support.

The economic situation in combination with the difficulties that the refugee families had to face when they settled in their new homelands, provided an opportunity for women to join the workforce of Greece. In many cases, due to widowhood or orphanhood, women’s work was the only source of income for the family household. The women refugees were mainly engaged in occupations that promoted the development of cottage industry, introducing, for example, carpet making to the Greek society. In Corfu, according to the census data, there were skilled seamstresses and workers, some teachers, farmers, and a woman sailor.

Γεώργιος Καγκουρίδης, Κέρκυρα 18/01/2022, Αρχείο Αναγνωστικής Εταιρίας Κερκύρας.

Μάρω Κατσαούνου, Αθήνα 23/05/2022, Αρχείο Αναγνωστικής Εταιρίας Κερκύρας.

Anastasia Chalkidou with her daughter Theodora Skordili, Garitsa, Corfu (1963).Nausica Mandyla Private Collection.

Carpet making tools and equipment. Nausica Mandyla Private Collection.

It is expressly forbidden to use, reproduce, republish, copy, store, sell, transmit, distribute, issue, perform, download, translate, modify in any way, partially or in summary, the content of the digital exhibition "From Ionia to Ionia" ", without the prior written permission of the Corfu Reading Society.